Piano-ing is different than Coding

Considering if hobbies, like learning to play piano, are worth it (in light of the Baumol Effect)

I recently started learning to play the piano. I've talked about how powerlifting is similar to programming, but in this episode, I'd like to think about why playing the piano is different than programming. More specifically, why composing music is different than coding, and why playing music is different than something running my code. I'll start by listing some important differences between the two, but then I'll describe a difference related to the Baumol Effect, and determine if that implies that learning piano is less worth it today than a couple hundred years ago.

The similarities are easy to come up with: you need to practice frequently to become proficient, general concepts from one instrument apply well to other instruments (analogous to programming languages), music is written in a certain notation and then executed/played, etc... But I've found that the differences are far more interesting than the similarities.

The analogs are:

Composing music or improvising <---> Coding

Playing music <---> Running a program (like a machine)

How composing music/improvising is different than coding:

- Bugs are fundamentally different. A composer won't accidentally create an infinite loop or a stack overflow. Sure, you could make a song repeat indefinitely (I guess), but you can expect a human player to not get stuck in this trap.

- The notation, or the code that is played, is not so removed from the outcome. In programming, there are always a million ways to complete the same task. Not so with music: There aren't a million ways to write the same song (if it's going to actually sound the same).

- Musical notation isn't always entirely sufficient. It's not uncommon to see phrases such as "gradually increase the energy", or "lively/with spirit", etc... I'm sure these phrases could be codified... it would just be inconvenient, since the machine running the code is a human who also understands English.

- It's desirable for different musicians to interpret a work differently. Otherwise composers would just make midi files (assuming a solution to #3).

How playing music is different from compiling and executing code (like v8 does):

- The performance of playing music is something people take pleasure witnessing. Concerts are only interesting if someone is playing the music there - live. This is in stark contrast to a web app - where the audience cares about what they can do with the executed code, not the actual executing of the code.

- V8 doesn't practice.

- You can't move your abilities to another machine. In fact, since no two people play the exact same way, we can't replicate any human performance across humans.

There are more interesting differences...

The Baumol Effect:

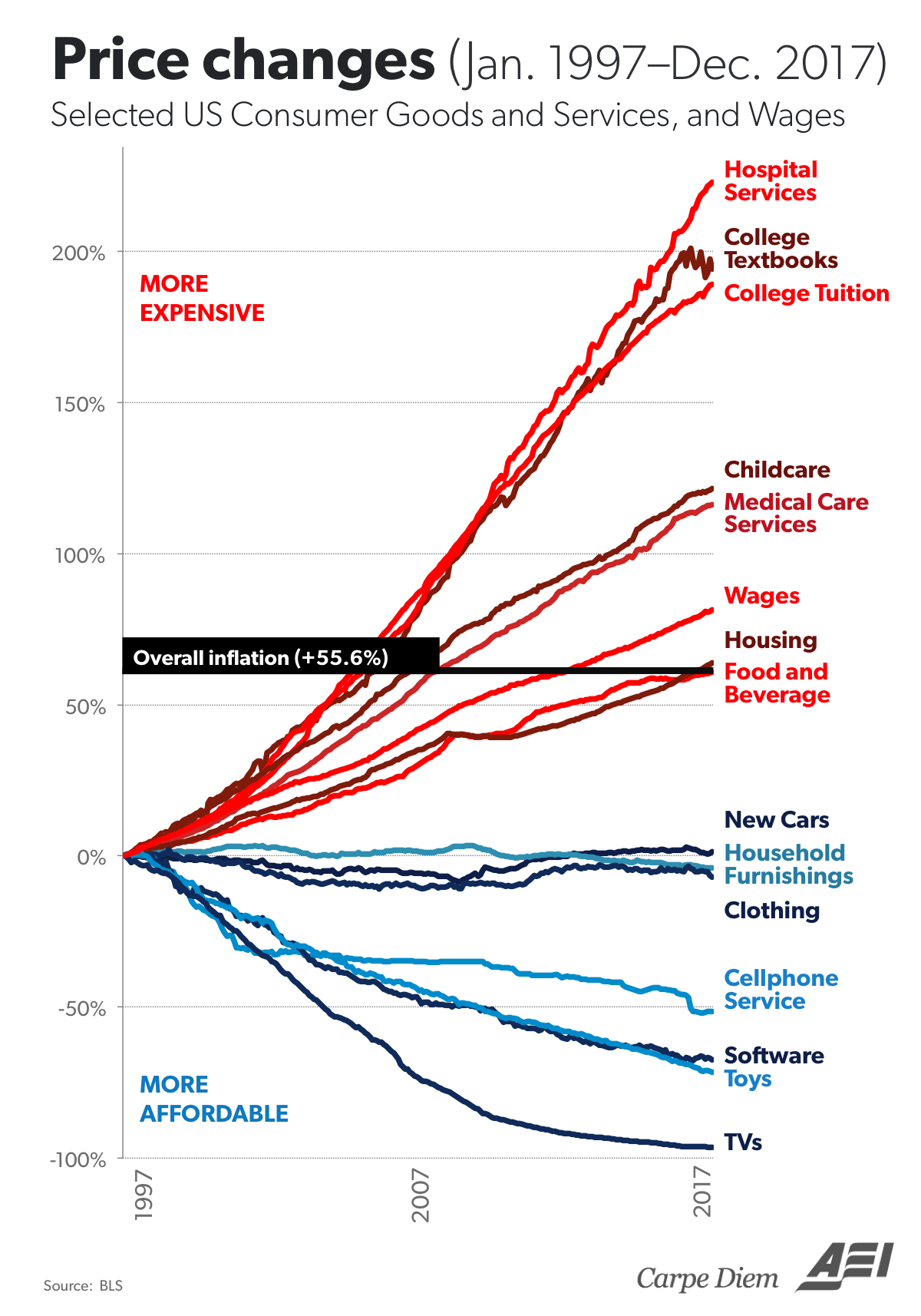

The Baumol Effect is something I learned about on The Not Unreasonable Podcast where Alex Tabarrok discussed his book Why Are the Prices So Damn High. He talks about why prices for some things have been going up since, say, the 1950s, while prices for most things have decreased. So while home appliances and telecommunications have become much cheaper, prices for education and healthcare have skyrocketed. Bernie Sanders might attribute this observation to greedy millionaires and shady pharmaceutical companies, but the less villainous Baumol Effect is probably the main driver here.

Alex gives an example to explain the Baumol Effect:

Take a Beethoven string quartet in 1826 - it takes 4 people 40 minutes to perform that string quartet. Now do the same thing today... It still takes 4 people 40 minutes to perform exactly the same string quartet. So in nearly 200 years, there has been no improvement in productivity in string quartet land. On the other hand, there are many, many, other sectors of the economy where productivity has increased tremendously. At producing goods... automobiles for example. Or at producing major appliances, in all of the areas which have made life so much better compared with 1826.

So if we go back to 1826 and we then compare: what's the cost of performing this type of task? And by cost, I mean what Economists call 'opportunity costs' - what do we lose? What does society lose when we have an additional performance of Beethoven's string quartet? Well, society loses 4 people doing something for 40 minutes. But in 1826, productivity in car production was so low, and in other areas of the economy, that that's a low opportunity cost. You're not giving up a lot, because those guys are not very productive at producing goods (they couldn't produce a lot - 4 people in 40 minutes). But today, 4 people in 40 minutes can produce a lot! In opportunity cost, it's gone from about $3 in 1826 to more like $70 in average wages. So the opportunity cost we give up has gone up, precisely because other sectors of the economy have become more productive.

So anytime you have a stagnant sector - a sector which grows slowly in productivity - the output of that sector will become more expensive over time, regardless of anything else.

I love this example.

My initial reaction was that the Baumol Effect makes it pretty clear that playing piano is not worth my time, since the productivity garnered out of it hasn't changed in centuries. And it's compounded by the stagnancy of piano teaching! Maybe teaching has gotten slightly better since 1820, but certainly nothing dramatic has happened recently -- I'm learning from a book published in 1998 after all. The Baumol Effect implies that Piano Teachers are getting more expensive as well.

In contrast, software (and by extension, software development) is "eating the world." Even since I've been a programmer, I've seen dramatic increases in the ease of creating, deploying, and scaling a web application, for example.

But this analysis is flawed for a couple reasons. First, just because other sectors are more productive doesn't mean that the wages of the less productive sector go down. Actually, that's what the Baumol effect is explaining. Although, if I care about GDP generally (which I do, but maybe not enough), then I guess I should pick hobbies that are increasing in productivity since the total output to others would be higher.

I should note that a quality electric keyboard, that accurately mimics the sound and feel of a full piano, has gone down, and the Baumol effect supports this notion. I can even plug headphones into the instrument so that I don't have to worry about bothering other people when I play. You couldn't do that in 1826.

But more importantly, playing piano is a hobby, and it's enjoyable because... well, the experience of learning and playing music is enjoyable! In the analogy to a Javascript engine running my code, the glaring difference is that v8 doesn't enjoy what it does, and that's what really matters for a hobby.

Playing piano has decreased relative to other sectors in productivity, but the personal enjoyment seems to hold it's own against newer forms of enjoyment that I believe offer less satisfaction, such as video games, social media, and streaming videos. That said, for my next hobby, I'll be keeping my eyes open for something that has increased in productivity, because increasing GDP may be our most important moral obligation. For now though, I'm ok with my time spent at the keyboard.