Software developers should learn from powerlifters

A large proportion of powerlifters are software developers. While there are a number of similarites between programming and powerlifting, the likeliest reason for the overlap is because of how similar the training process is. But the differences in how they train are even more interesting, because that's where an untapped market can be found.

If you've spent much time in a powerlifting gym, you've probably noticed that many lifters are also software developers. What makes a sport that consists of "lifting the heaviest weights possible" attract people who otherwise sit at a computer all day? A likely answer is that the training/self-improvement process is essentially the same, with only a few key caveats. One such caveat suggests that powerlifters have exposed a major blind-spot in the current software developer learning process.

Good programmers who don't focus on continuing education simply don't exist. This is true of many professions, but software devs in particular deal with the added complexity of working with a wide range of ever-changing technologies - so adaptation and learning is the name of their game. If a programmer doesn't like this aspect of their profession, then they won't last long. Or they end up writing Python 2.6 code for fixed income swap trader's P&L reports at Bank of America (I've unfortunately seen this first hand). But I digress...

Focus on continual improvement is also vital for powerlifters. In fact, it's more extreme: if a powerlifter doesn't continually build their technique & strength (analogous to software developers' skill & grit), they lose both. Indeed, a sizeable literature has developed around the science of "periodization" which refers to strategies for organizing training, and making decisions about when and what type of stress you place on the body.

How Powerlifters Train

Most elite powerlifters log all of their workouts to share with a coach. Coaches utilize various techniques, along with this data, to program optimal workouts for the athlete's development. Athletes without a coach are generally not elite (so are less willing to pay for an edge). They have to create their own periodization schemes (known as powerlifting programs), or buy templates that have been built by pros. Indeed, a large industry has emerged to fill this need. Starting Strength is the most popular, but I recommend barbell medicine for a more evidence-based approach. Of course, these are no replacement for a coach who can focus on the unique aspects of each athlete, allowing the athlete to focus on completing (as opposed to creating) their workouts.

The Seven Concepts of Periodization

The principles that are used to create a powerlifting programs consist of roughly seven concepts:

- Stimulus-Recovery-Adaptation

- Overload Specificity

- Variation

- Fatigue Management

- Phase Potentiation

- Individual Differences.

Describing each concept is beyond the scope of this article, but I encourage you to read about them, since the application to personal growth and learning is clear as day.

In fact, these principles could have come straight from Barbara Oakley's wonderful A Mind For Numbers -- in other words, the principles that make your body stronger and more skilled have synonymous concepts in the current literature for learning and memory. No, Ms Oakley didn't write about these concepts specifically - the point is that she could have, and it would have been valuable.

All this said, your mind and your body are not identical, and strength doesn't have a perfect parallel for programmers. So the analogies break down at some point. Let look at the most obvious ones...

The first difference (and why it doesn't matter): Peaking

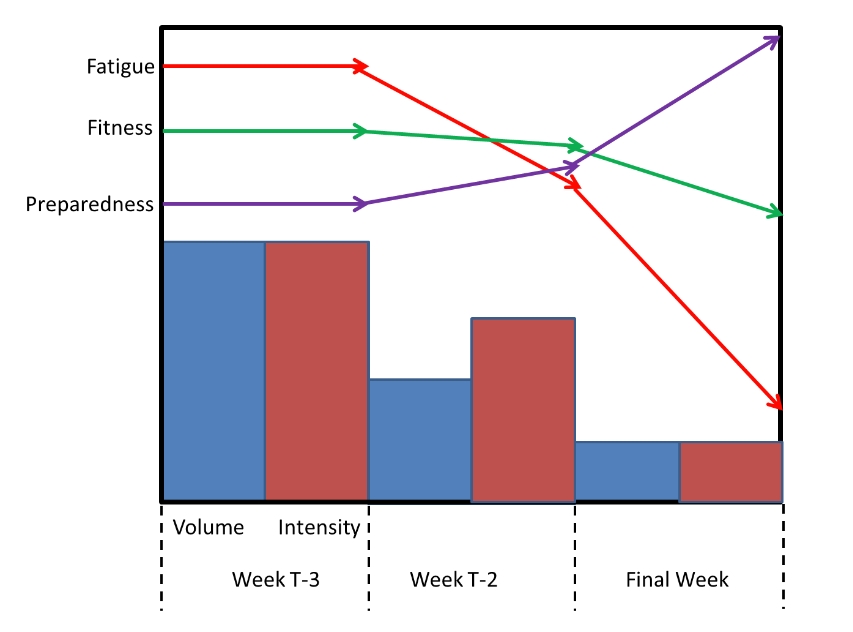

In general, powerlifting programs will decrease the amount of work an athlete performs as a competition approaches. This is known as "peaking" -- an athlete sacrifices some fitness in exchange for lower fatigue. When done correctly, this is a trade-off worth making:

It's not clear that an appropriate analogy can be drawn to software development learning practices. I could try to find a similar concept (I did try), but it's not worth it. Software developers don't need a "peaking" stage.

The other difference (and why it matters)

If there is one place where training to be a better software developer vs powerlifter is fundamentally different, then maybe something can be learned from one of the groups. And it seems that powerlifters as a group have figured out something that software devs haven't caught onto yet... Powerlifters hire coaches.

Elite powerlifters hire coaches because they need to focus their efforts on becoming as strong and skilled as possible -- the complexity of creating an individualized periodization program is better left in the hands of someone who does that professionally (this seems obvious). Coaches want to build resumes of impressive athletes -- this benefits lifters who get workout plans and feedback from someone who has "skin in the game".

Almost no programmer thinks the training provided by their employer or coworkers is any good (if you do, I'd love to hear from you). The social structures that support growth as a programmer aren't sufficient, and for many, don't exist for continuing growth after graduating from school. Agnes Collard, a philosopher who wrote a book about 'aspiration' recently said,

University makes it possible to throw people into an environment with the thought "I want to become something." And that thought is productive, in a way that it often isn't when you sorta "go find yourself". Because when you "go find yourself in Europe", there isn't an institutional structure that is in any sense guiding you so that you get somewhere. But at universities, you are being guided, in a very gentle way, and there's so many ends you could pick, that even if you don't know where you are going, you could be going somewhere.

The only place I know of that provides such a support structure is Recurse Center, which I can't speak more highly of, but it comes with the opportunity cost of 3 months without a professional job and relocating to NYC, which is why most programmers haven't taken advantage of it.

So there isn't, yet, a significant industry of ongoing professional-development coaching in the software development space -- Unlike my peers in powerlifting, I don't have peer programmers who have coaches. Nobody that I know of is paying a professional to lay out individualized systems for their continuing education, or getting feedback from someone who is incentivized by their success. Something like this exists for people beginning their career (Lambda School), but not for current professionals. Today, it is left up to the programmer to find the next best things to learn, strengthen their foundations (GPP), use "progressive overload" to continually work on harder problems, control for fatigue, craft it for their individual interests/strengths/weaknesses, and have an appropriate level of focus on specificity and variability.

If this sounds difficult, that's because it is. Which is precisely why there should be an industry of people who do this for a living. It's absurd to leave all the planning up to the person who needs to focus on the learning. So there is a market waiting to be built. No, online classes are not the answer: only 5.5% of online courses are completed.

Individualized training, supported by someone with skin in the game, is a hard business model to scale. But someone is going to do it. Powerlifters have already figured it out. In the world of software development, who is going to get there first?