The Fermi Paradox and what matters

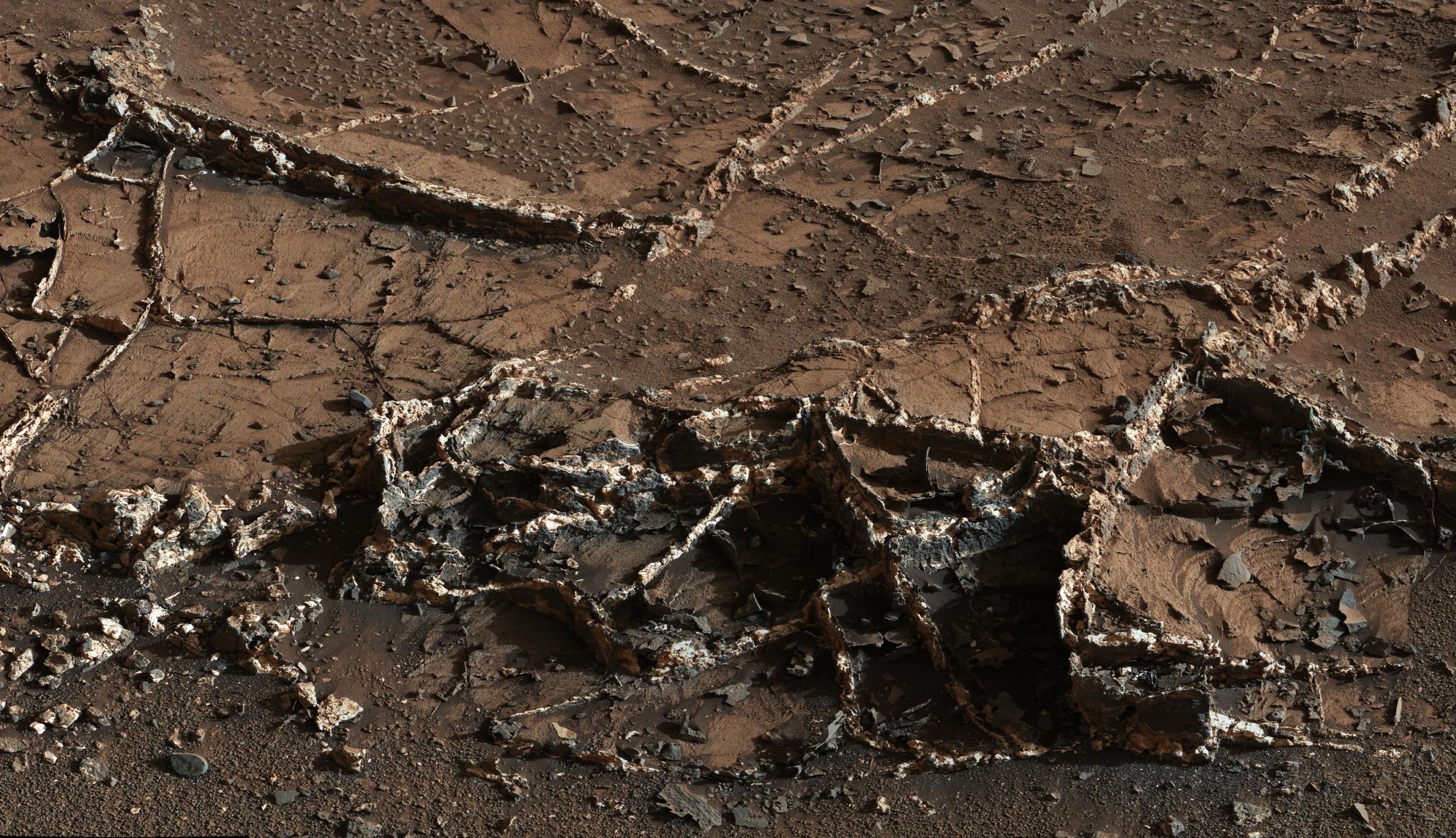

Is there, or has there ever been, life on Mars? Nope. We can't find evidence of it with rovers, landers, or satellite imaging. Sure, we haven't sampled that much soil, but keep in mind: it's nearly impossible to find a square foot of Earth's surface that isn't teeming with life. As far I can tell, life is like glitter: where it exists, it gets everywhere.

But what about intelligent life, elsewhere in the universe? It seems that with enough time, intelligent life might also be analogous to glitter: if we don't see evidence of intelligent life out there, then it's not there. Wouldn't intelligent life have spread so much that it would be impossible to miss?

Some people believe that we already have good evidence of alien intelligent life. Maybe the Alex Jones theory of the universe is correct: there are inter-dimensional beings (elves and such) that permeate our world, and they can be communicated with when a "gate" in our consciousness is opened up by hallucinogens. Or maybe some UFO sightings are real. I give the combination of these possibilities < .005% likelihood. Why so low? UFO sightings have gone way down now that we carry cameras around, and it's silly you had to read that sentence with Alex Jones's name. Sorry about that. So given essentially zero evidence of alien intelligent life, let's examine the Fermi Paradox, and what it means for us.

Back-of-the-napkin Fermi paradox calculations (skip if familiar):

The universe is 13.8 billion years old. Earth formed 4.5 billion years ago. Life on earth started 3.5 billion years ago. So just one billion years between the formation of earth and the first signs of life.

Earth has existed for about 1/3 the age of the universe, but earth-like planets have existed since nearly the beginning: 12.8 billion years ago seems to be a realistic estimate for the first life-supporting planets. A very long time.

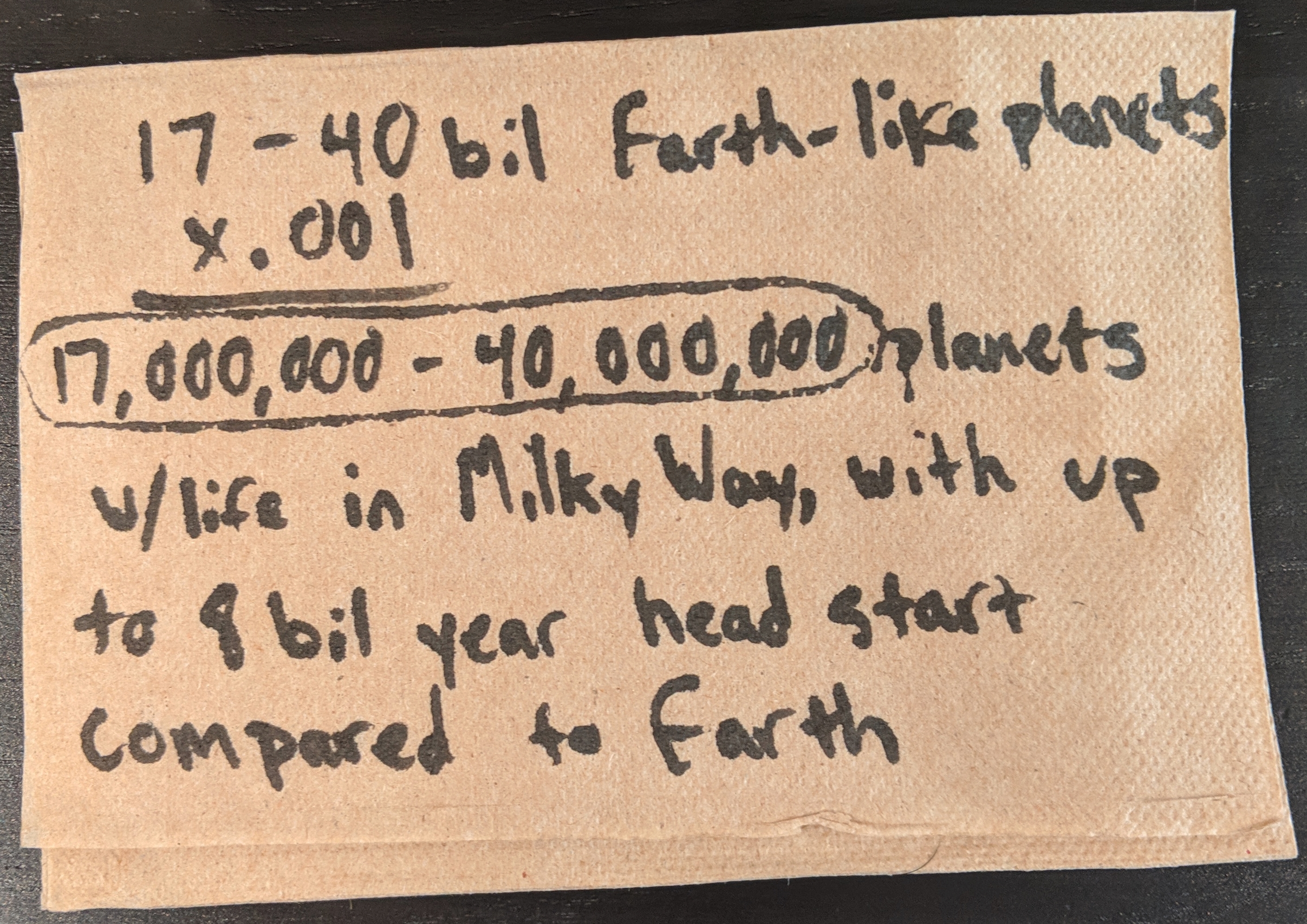

There are two trillion galaxies in the universe today. I find this number to be even harder to wrap my head around than 12.8 billion years. So, for the sake of my napkin, let's disregard this number and focus on just our local, one in two trillion, Milky Way galaxy. How many planets are earth-like in our galaxy? Current estimates are between 17 billion and 40 billion earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones of Sun-like stars and red dwarf stars within the Milky Way galaxy.

To recap: the formation of life-supporting planets started 12.8 billion years ago (8 billions years before Earth), and 17-40 billion of these types of planets are in our galaxy. If life happened in only 0.1% of those planets, then there would be 17 to 40 million planets in the Milky Way that have been lived on, and essentially all have had a vast head-start on Earth.

The Fermi Paradox is essentially the question, "Given the billions of years of head start that billions of life-supporting planets have had in our galaxy, why haven't we seen any evidence of life? Shouldn't signals be visible everywhere? Shouldn't our galaxy be teaming with spaceships? Shouldn't sophisticated life that existed billions of years ago have left evidence of their existence, like huge clusters of dyson spheres?" What is going on?

Some solutions

The Fermi Paradox is a popular thing to theorize about, so a bunch of "solutions" have been posited. Among the most popular are:

- We've just missed the signals. Billions of years have gone by in which intelligent life could have sent signals, but we have only had technology to intercept signals, such as radio waves, for mere centuries. The signals came and went.

- We aren't worth communicating with. Super intelligent species are communicating on another level, and see no reason to use primitive technologies like radio wave.

- Traveling isn't interesting. Sending something at super fast speeds (even light speed) isn't worth the effort. It would still take potentially thousands of years to get to other intelligent life, and then would take just as long to send a signals back. There are better things to do on the earth-like planets than reach out to others or spread throughout the galaxy.

- A number of technological "filters" exist ahead of us, and all other intelligent life has been destroyed by such filters, before getting to the point of broadcasting their existence. This is a scary one, made popular recently by Nick Bostrom. Essentially, at some point we will discover a technology that destroys us, (through something like nuclear war, climate change, or AI), and suffer the same fate as all other intelligent life. Extinction is inevitable, and it's coming soon.

Of these, I think the last one is the most compelling, because the others don't take into account the lack of physical objects that we would expect to see floating around (like the aforementioned dyson spheres).

But I think that the best answer to the paradox was written by Sandberg, Drexler, and Ord. Unlike the other solutions I listed above, SDO don't claim that intelligent life exists and we are just missing their signals (or that it existed but destroyed itself). Instead, in their paper, my estimate of life happening in "only 0.1%" of earth-like planets is ridiculously high. By using "models of chemical and genetic transitions on paths to the origin of life" in a "synthetic point estimate" model, they find "a substantial probability of there being no other intelligent life in our observable universe" (read more on SSC). So it's not a paradox -- it's just supremely unlikely for life to exist, and we shouldn't be surprised that we are the only intelligent life in our corner of the universe. This does not mean that life is not out there somewhere, just that there isn't much of it.

If we take this seriously (which I think we should), and say that we are probably alone in this side of the Milky Way... does this matter? Well, what matters? As far as I can tell, what matters, or what has meaning, is determined by how we connect to the world. And we connect to the world through relationships.

What is a relationship?

Let's start by considering a two person, loving relationship. Other types of relationships are also valid, but this type is easier for most people to relate to. We can think about other types of friendships with arbitrary amounts of participants in the same way.

I used to think of relationships as existing within each person. Under this model, affection, commitment, and support for the other person is essentially "repaid" by the other. So each person gives and receives, which can be mutually beneficial. In a sense, it's a market that exists between the individuals, and its currency is the things that make a relationship worthwhile to the other. This is a useful model for examining relationships on a superficial level, but it's inadequate on closer inspection. Economist Tyler Cowen debated Philosopher Agnes Callard on the use of markets to model gift-giving, and he wins the argument, but I think he's missing the deeper point about why relationships are useful. Agnes knows that there is a deeper level to gift-giving that the economic model isn't taking into account, but she doesn't articulate it. I'll try to do that.

I've started thinking about relationships existing, in a sense, outside of the individuals - through a shared vulnerability (not a market). A specific, spatio-temporal vulnerability in the world.

The vulnerability comes from the realization that our allotted time is short and fleeting. "I will die. Maybe today!" When this is a conscious realization, our vulnerability becomes a blatant fact, although it doesn't always have to be so conscious. But we have to do something about it, or risk becoming alienated by it. The answer is simple - we learn to share it.

This is why we have relationships, and this is what relationships are. Through sharing experiences, events become meaningful, because each person cares about how the events affect the other. It makes people close and connected, not just to each other, but to the world. The world, at a specific time and place, becomes more significant. More meaningful. This is why being close to someone feels so good: because it is good! It makes the world meaningful.

Relationships are also forward-looking. A strong relationship should compound -- 'meaning' should be built out of 'meaning'. In other words, life becomes more meaningful because previously shared events were meaningful. And this compounding only works if each person understands the other. And cares, and worries about, and wants the best for the other, unselfishly. Unselfishly, because the commitment to the other is not something that the other holds them to -- it's something each person chooses for themselves. Then the couple can be honest with each other, which means their shared vulnerability to life and the world is real and unambiguous. I think this is how love works.

Like the "relationship is a market between individuals" model, there are, of course, still mutual benefits to the individuals in this alternative model. The primary difference is that "meaning" is central to the relationship, and the benifits are far greater. "Closeness" is valuable not for what each person gets from the other, but for connecting people to the world.

This model actually sounds a lot more like religion than I anticipated, but that makes sense. In fact, under this model, religion is another type of relationship -- it's another way for meaning to be built out of shared experiences, by starting with a common belief system. We can even think of good deeds, like charity, or building a better future, as a form of sharing our vulnerability. Charitable acts share the burden of vulnerability with those who are weighed down more heavily.

When a relationship fails, this shared relation to time, place, and the world, is crushed. The "meaning" tied up in memories is rooted out of the past, leaving events that can be nearly impossible to rearrange into something coherent and worthwhile. This is why a couple that grows old together is so beautiful (if they do so freely). And why a breakup is so tragic. It's why a relationship is worth fighting for. It's also why lying is wrong. Because our connection to the world has to be built on something real. And it's is all we have. If we lose it, we become alienated, and if it grows, we become more of a part of the world. So if the love is deep enough, if the shared vulnerability was and is honest enough, then it's not that "love is worth fighting for." Rather, "meaning is worth fighting for." So love stands a chance.

It is really everything?

I have an acquaintance who did way too much LSD earlier in his life (he says he is still stuck in an acid trip from 30 years ago). He often opines that "Love is everything." This is a common refrain among serious mystics as well. A key phase of Christian mysticism sounds remarkably similar John 4:16: "God is love, and he who abides in love abides in God and God in him." A good friend of mine tried to dive into this with me: Why do people say this? Where does the primacy of love in spiritual events come from?

Spiritual experiences feature an intense feeling of being connected to the world. This closeness -- the feeling of being part of the cosmos (or God), or of unity in the world -- is associated with love. This makes sense in the model of relationships being about a shared vulnerability, where meaning comes from the fact that it's both (or all) of yours. That you're in it together. The world becomes meaningful when your experiences are part of it.

But if love loses, as it sometimes does, then it can't be everything, right? Right. Relationships are real and are more than biochemical signals in brains or markets between individuals. They exist because we are vulnerable creatures with fleeting lives, which entails that it's not all love. And of course, if everything is love, then where do Nazis fit in? Notice that John 4:16 said "God", not "everything" is love. "Love is everything" is maybe just using slightly wrong words. Maybe "Through love, we can find meaning in the world, and that's all we have" is closer to the truth. Not as catchy though.

And what about aliens?

Thinking about the Fermi paradox is a neat trick to get us thinking about vast amounts of space and time. Two trillion galaxies exist in this 13.8 billion years-old universe, and just our own galaxy has billions of planets that are similar to, but far older than, Earth. That should make us feel insignificant. But nevertheless, we are part it, and our insignificance is kinda the point. As long as we remember that, our relationships should only become more vital.

Earlier, I asked if it matters if alien intelligent life exists or not. I waver a lot on this question, but I think the answer is no, unless we can interact with them - really share an experience with them (or get destroyed by them). Or if it matters to religious doctrines. Our relationship to the universe wouldn't change that significantly just because experiences happen in places other than Earth. Because if aliens exist or not, we are all we've got. "It's hard on the body. It's hard on the mind. To learn what kept us together, darling, is what kept us alive."